I Saw the TV Glow and I couldn't look away

The horrors of being trans and the joy of seeing it put to film

Each year, with the turning of the tides and the leaves changing colour before falling onto the cold ground, I get reborn in warm hues of orange, brown and yellow. After September made me feel stuck in a black hole, I was instead welcomed by the neon colour palette of Jane Schoenbrun’s I Saw the TV Glow. Their film slowly pulled me out of my slump, only to drop me face-first into an oversaturated freak show that left me feeling both seen and unseen.

I first saw the film in the company of my best friend. We were sitting next to each other on my new powder blue Ikea sheets after not seeing each other in over a month. I was too scared to watch it alone. In general, I’m not one to watch any horror by myself; I wish to avoid spoilers, but I also want to avoid getting triggered and being left alone to wallow in my misery. I Saw the TV Glow wasn’t frightening to me because of the body horror or the man in the moon—the ice cream man even made a nervous laughter erupt from within me; he kind of reminded me of the album cover for Blur’s The Magic Whip too. The thing that’s so scary and utterly mortifying about I Saw the TV Glow is actually how close to reality it is for many trans people, including myself.

Director and writer Jane Schoenbrun describes the plot of the film as the moment the ‘egg cracks’ for many trans people. The moment you realise the gender you were given at birth doesn’t align with who you are. The thing you were gifted at this joyous moment was more of a dead sentence, a burden, than a present.

The contents of my egg spilled a long time ago. The delicate marble started to break open when the first lockdown happened in March 2021, leaving a mess I am still working towards cleaning up every day. Better yet, I am still finding out in what ways I can pick up this grotesquerie, polish it all up, stick the pieces together, and make them shiny once more. Three years ago I started experimenting with my hair, my pronouns, the clothes I wore. For once in my life, I liked the way I perceived my form and how it was perceived by others, but I was aching to feel the same on the inside. Only the people in my closest circle knew at first—mainly people I met through various internet communities and my closest loved ones—but once that egg cracks, it’s impossible to keep the goo from spilling onto the floor, to keep your new identity hidden when it’s aching to come out.

I started seeing a therapist for the first time in my life and felt a form of relief, short-lived, because I soon realised I would have to tell my parents. Their daughter would be changing; I tried to make it easier for them, peeling the egg as slowly as I could, a process I’m still in the midst of, but I’m afraid of the repercussions I will face once the yolk is truly exposed and threatens to seep through my fingers.

What terrifies viewers like me is the way the film shows how brutal it is when you slowly come to the realisation that you’re trapped in a body that isn’t yours. That mental fog you cannot seem to escape out of, wanting to retreat into yourself but finding out it’s not safe in there. Feeling tormented by your own brain, plagued by gender dysphoria, is a harsh reality I have to face every single day. Each morning I wake up, terrified of opening my bedroom door and being perceived by others. I can’t escape inwards; that’s where my dysphoria houses itself. I can’t escape outwards; it’s where my body resides. The only time I feel remotely safe is nestled within my favourite piece of media. Not unlike the two main characters, I live vicariously through fictional characters and music. That catharsis that a trans person gets from doing something gender affirming—whether it’s getting top surgery, taking hormones, wearing clothes you like, or someone using the correct pronouns—films give me that feeling most of all. I felt it watching Gregg Araki’s Teen Apocalypse Trilogy and I felt it again during I Saw the TV glow. The horrors of being trans plague me at this moment in my journey, but if this was a happy film, I don’t think I would like it as much.

There’s a certain passivity to the film, leaning on its atmosphere and dialogue with the occasional scare, but once it escalates and explodes into neon, it’s like you’re getting pushed by an unseen hand further into the cold, dry dirt. That feeling of passivity is undeniably tied to the trans experience; it’s the red thread keeping you from losing the way forward on the path you’re on during these horror years. I’ve been actively fighting that passivity, and it feels like I’m losing my fight. You get put on a waiting list at your hospital, the first speck of dirt lands on your face, and you keep following that thread. Slowly, moss and veins start to grow beneath the soles of your feet; they start to crawl up, and walking becomes a task when it used to be mere routine. Finally, you hear the static calling you, a call from the hospital, beckoning you forward, but the vines have grown into branches, and like a tree, you are stuck in one place until someone cuts you down and spreads your seeds somewhere else.

The year is 1996; we meet Owen and Maddy when they are both going through the worst time of their lives: high school. Owen—the younger of the two—notices Maddy as she’s sitting alone, reading the episode guide of the fictional television show The Pink Opaque. We’re quick to notice that Owen regards Maddy as a role model; she’s cool, mysterious, and they clearly have a common interest in the show. But just like Owen, Maddy is isolated from her peers, which ultimately draws the two towards each other. It’s a cheesy, overly awkward meeting, but it’s true and pure nonetheless.

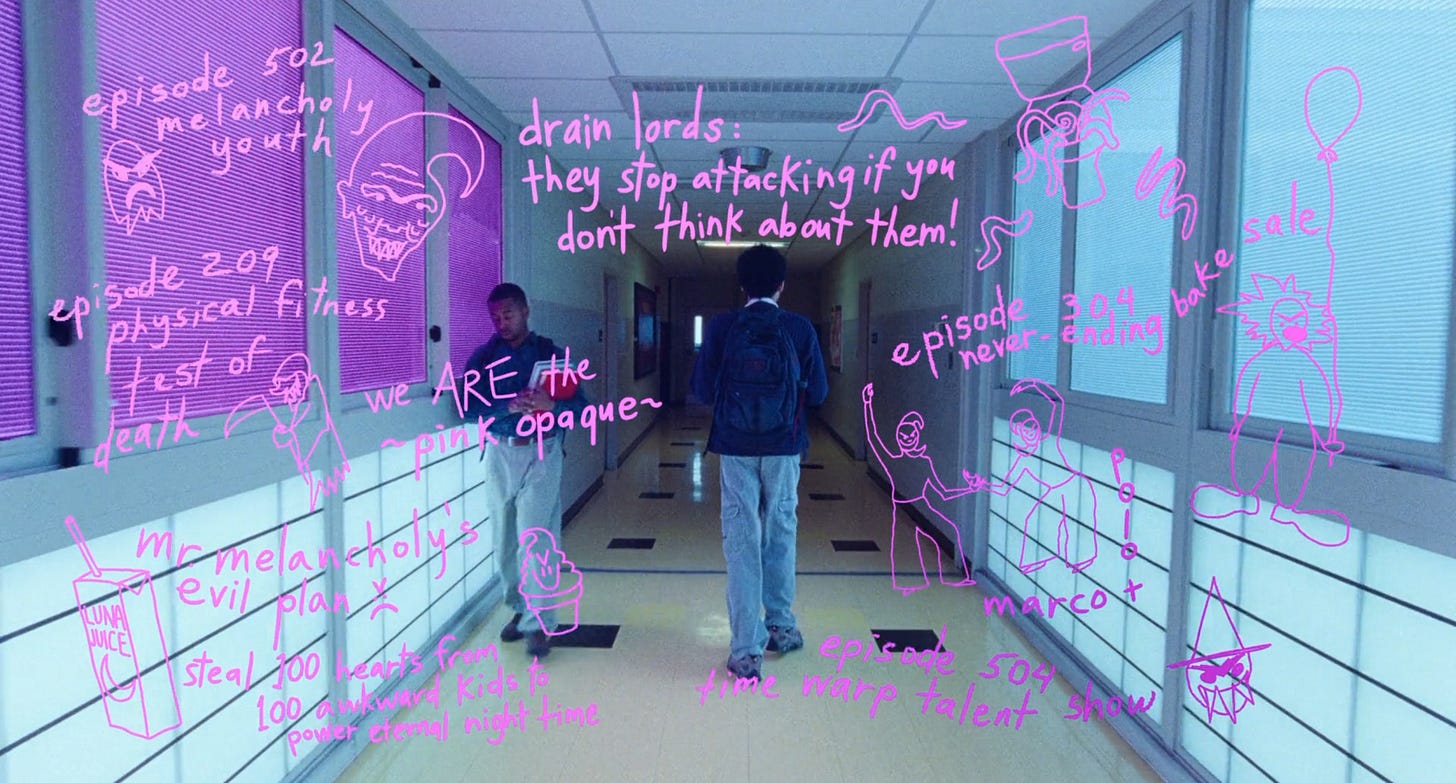

The Pink Opaque centres around two teenagers named Isabel and Tara who use their psychic connection to fight the villain Mr. Melancholy, who has the power to warp time and reality. Owen's father Frank derides him for watching the show, calling it a ‘show for girls’ while his mother makes Owen adhere to his 10 pm bedtime, right before the show airs. The show is something out of reach for Owen, just like his true self—always looming somewhere out of view. Maddy feels deeply connected to the show, finding it feels more ‘real than real life’ and is happy to have found fresh meat to introduce her favourite show to. Owen gets around his parents’ strictness by planning a sleepover with Maddy under the guise of staying with an old school friend Owen lost touch with years ago.

The connection the teens have towards The Pink Opaque only grows deeper and slowly blossoms into an obsession, a fixation. Reality starts to blur two years later in 1998 when Maddy disappears, Owen’s mother passes away from cancer and The Pink Opaque gets cancelled. It’s not just the viewer who loses their grip on the narrative; so does Owen.

Maddy leaves tapes of the show in the dark room at school for Owen to take home and watch; the two barely communicate face-to-face, instead opting to talk through notes we see plastered on the screen during the montage of Owen walking through the busy school halls. One scene shows the two share a rare conversation while on the bleachers during recess; Owen asks Maddy if they can have a sleepover again, wishing to watch The Pink Opaque when it airs instead of on tape. Maddy shuts it down at first, telling Owen she’s into girls, misunderstanding his intention. She questions Owen about his interests, “I think that I like TV shows.” He says. “It feels like someone took a shovel and dug out all my insides. And I know there's nothing in there, but I'm still too nervous to open myself up and check.” He continues, foreshadowing the path he is about to go down.

During their sleepover, Maddy reveals plans of running away from her absent mom and abusive stepfather and prompts Owen to go with her. The two share a tender moment afterwards when Maddy draws the ghost tattoo the characters of Isabel and Tara both have on the back of their necks, sealing their connection. Later on, in a panic, he knocks on the door of his ex-friend’s house and confesses he’s been lying about staying there when the mom answers.

As we grow, our perceptions and attachments to the media from our youth grow with us. I Saw the TV Glow delves into this concept by showing two different iterations of The Pink Opaque outlined by the changing of Owen’s self-perception, reflecting a shift in his perception of his gender identity and the shame and dysphoria that gets paired with it.

Like any other (in)sane person, I keep searching in what way I have attached myself to the media I watch; in this case, I felt a clear connection to my experience of being on the spectrum. I’m currently in the process of getting my autism diagnosed, and I have felt myself retreating back into my biggest hyperfixation to date: Twin Peaks. During our watch, I exclaimed multiple times to my friend how certain scenes reminded me of my favourite show—my uncertainty regarding this notion being made up or projected onto the film by my obsessiveness got shut down after reading an interview1 in which Schoenbrun confesses to drawing inspiration from a recurring dream about the ending of Twin Peaks—aiming to capture a ‘Lynchian terror.’ As well as reminiscing on themes of endings and revivals, inspired by the third season Twin Peaks: The Return which aired 25 years after its cancellation.

What inspired The Pink Opaque, though, was Schoenbrun’s very own obsession with a TV show from their youth, namely, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, featuring similar elements like a strong female lead, mysticism, and the familiar monster-of-the-week episodes with the film’s characters of the ice cream man and the ultimate villain: the man in the moon. Is the man in the moon another embodiment of God, and is him trapping Isabel and Tara in a pocket dimension a metaphor for the body he traps us in?

The magical but slightly eerie world of I Saw the TV Glow is maintained through the collaboration of cinematographer Eric Yue, colorist Mikey Rossiter creating monotone spaces by honing in on a single color in certain scenes and the SFX team who crafted the monsters within The Pink Opaque by relying on practical effects. The sudden appearance of the ice cream man, Mr. Melancholy’s halfmoon-shaped henchmen performing their bone-chilling dance, and the big bad: Mr. Melancholy—the infamous man in the moon himself—a distorted and demented vision of blue coming to swallow you whole.

It’s unknown to me whether Schoenbrun is on the spectrum themself; nevertheless, it felt all too familiar seeing the deep emotional attachment Owen and Maddy have to The Pink Opaque. Your reality—the one existing in your head, your truth—morphs with that of the subject of your hyperfixation, almost. When that gets taken away from you or disregarded, that reality starts to crumble.

Identifying with a TV show is a way for me to secure my own identity, my own ‘being human.’ It’s hard enough to try and fit in with a society that isn’t built for you and, even worse, does everything in its power to exclude and sometimes even shun you. Finding one where you do fit, whether it’s in the quaint town of Twin Peaks, The Pink Opaque or Sunnydale, is a form of survival. Once you’ve gotten to know and grown attached to a fictional character, they’re a part of you, and you’re able to live through them, something you cannot do with real people. It’s also easier to read these fictional characters, something I struggle with in my day-to-day life. I’m able to read a character like Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks because I relate to them; I have seen their journey, and it has become mine because I went with them on said journey. Rewatching our favourite media is a way for autistics to stay grounded, because we can predict what’s going to come; we know these people aren’t going to hurt us the way real people do because we were side by side on their journey to solving Laura Palmer’s murder or slaying vampires.

A flash forward to 2006 reveals Owen still living at home, working at a local movie theatre. After years of routine and mundanity, Maddy reappears suddenly when Owen is at a grocery store, and they catch up at a bar near the edge of town where different bands are playing. She has a noticeably different look, something maturity is only partially responsible for. Maddy questions Owen about his memories of The Pink Opaque, telling him the strange tale of having lived in the show for the last eight years. “Do you remember it as just a TV show?” She questions Owen, the scene cutting to a flashback of Owen in a pink slip dress identical to the one Isabel wears. The two realities clash together, time moving abnormally. “Do you ever feel like you’re narrating your own life?” A clear nod to the fourth wall breaks of Owen narrating his story to us. “I’ve been there, inside the show, inside The Pink Opaque.” She concludes as the film cuts to the second performance of the night: ‘Psychic wound’ by King Woman.

The soundtrack of I Saw the TV Glow is as much a part of the film as its characters; it’s a living entity, a glow protruding from behind your eyelids. Existing songs curated by Schoenbrun form the outer layer of this bubble we float in for 100 minutes. The hubris of teen angst wrapped up in a 90’s package with femme and queer artists at the forefront. It’s Schoenbrun going back in time to their teenage years, crafting mixtapes in the secret static of their TV screen playing MTV commercials. It’s a sum of new and old, the past and the future, existing songs and songs written to capture the same feeling of teen angst the film portrays.

The score created by Alex G hits you when you least expect it. The string parts especially form a pit in your stomach, stirring something buried in an unknown part of your body. It invites us inside a vast unknown darkness, a deep bellow sounding from below the chalked-up streets—awakening something yet to be named, yet to be discovered.

Maddy convinces Owen to rewatch the series finale in which Isabel and Tara are imprisoned inside a pocket universe by Mr. Melancholy. Tara gets buried alive before Isabel gets kidnapped by Mr. Melancholy’s henchmen. They cut out her heart, feed her luna juice—a’ poison that stops Owen from remembering who he is, her real name, her superpowers, her heart; she won't even remember that she's dying. And they bury her, too. This reveal sends Owen into a frenzy, causing him to smash his head through the TV screen in a moment of crisis, getting pulled out by his father.

They meet one last time at the high school where Maddy tells the story of what happened to her. Of using a new name. That running away didn’t automatically fix her. Nothing ‘magically aligned’ after leaving their bleak suburbia behind. Still feeling unsatisfied and ‘asleep,’ Maddy paid a man to bury her alive, suffocating before awakening in The Pink Opaque as Tara. Owen loses his nerve once more after Maddy urges him to start the sixth season of the show by going down the same path as her. After their encounter, Owen runs home, never seeing Maddy again. It’s no coincidence the name Tara means ‘earth’.

Four years later, in 2010, Owen’s father passes, and his boss transfers him to a family entertainment centre. Still haunted by the words of his former best friend, Owen rewatches the show that haunted his teenage years but finds it more childish than he remembers. It’s almost laughable how silly this version of The Pink Opaque looks as compared to the one both viewer and Owen watched in the nineties timeline. The show that initially looked like an ode to teen television of the nineties now looks like an overproduced Netflix show for children that were born with an iPad in their hands.

The pit Owen is in only increases as his asthma worsens simultaneously. We now find ourselves in 2026 as the film comes to a crescendoing climax during a birthday party at the family entertainment centre. Owen starts spiralling, finding himself in the midst of a panic attack, screaming, “You need to help me! I’m dying right now!” only getting met by complete ignorance from his bystanders and he apologises. He flees to the bathroom, locking himself inside, vomiting a blue substance strangely resembling the luna juice before slowly cutting his chest open with a Stanley knife. He opens himself up in the mirror—getting greeted by TV static glowing from inside. He smiles and leaves the bathroom, hurrying back to work while apologising profusely for his outburst, unnoticed once more.

Schoenbrun very consciously chose to not make their script show the coming-out experience or transitioning explicitly, opting to keep it entirely allegorical. They began working on the script three months after they’d begun undergoing hormone replacement therapy, described as being amid “overwhelming calamity” after having come out as transgender.

The scene where Owen and Maddy meet again for the first time is a clear visual representation of the two different paths in their trans-ness these characters are on. Maddy not only looks different; she also exudes a certain comfort in her own body and being, one that Owen doesn’t possess yet. Regardless of one's choice to transition or not, this represents the state of realising one’s transness and filling out the way an individual wishes to express this.

Owen and Maddy represent these two stages trans people find themselves in: the pre- and post-egg cracking. Owen isn’t a hero in his story but a victim, being disconnected from reality and struggling to hold on to the magic the show from his youth used to bring in the face of adulthood.

The film’s ending shows the indifference of the world to his call for help; something inside him is dying, and nobody bats an eye to this revelation. Schoenbrun wishes to highlight the importance of “a little magic, borrowed from art [being] one of the only ways to survive.”2 The egg cracking might implode your life, proving the space you live in to be uninhabitable, but pushing that feeling down will only result in a quicker decay.

Owen is still buried up until the ending, seemingly having asthmatic fits when in reality he keeps choking on the dirt from the grave he keeps sinking deeper into. The sound design in these last few scenes is a standout, showing Owen gasping for air every few seconds, reaching for his inhaler in search of solace but never quite reaching the security this blanket is supposed to give. His choice to not bury himself alive is destined to kill him. By keeping his transness buried, by keeping it hidden, Owen robs himself of the life he deserves to live, the life he has to live to survive. The choice to end I Saw the TV Glow this way illustrates Schoenbrun’s fear of potentially living out a life without having transitioned. Owen’s journey isn’t ending when the credits roll; it’s only starting. By opening up his chest, his egg cracks, revealing his true form being born and trying to crawl out from its cavity. But we mustn’t forget that the person you are under the dirt will find a way to the surface; the egg is bound to crack one day. If you refuse to let yourself be resurrected, you are bound to run out of air and become fully engulfed under the dirt, but until then you have time.

Now I want to watch it!